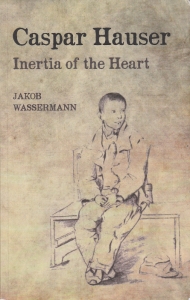

I first heard of Caspar Hauser from the 1974 Werner Herzog film, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, which I probably first watched in the early 1990s. I would imagine that for many of us this was our first encounter with the story. Jakob Wasserman’s novel, Caspar Hauser: Inertia of the Heart, which was first published in 1908, did a similar job as the Herzog film in popularising the story of Caspar, which is based on real events. It’s worth checking out the Wikipedia page if you are interested in discovering the historical facts of the case. I always find it difficult with fictionalised versions of real events because it’s always tempting to check the fiction against the historical events, which I have done whilst reading this novel, but with this review I will try to stick to what is solely contained within the novel. I shall also use the spelling used within the novel, i.e. ‘Caspar’ rather than the more commonly used ‘Kaspar’ but I shall avoid using the spelling of ‘Nürnberg’ for ‘Nuremberg’ that is used in the book except when I’m quoting from the book. The edition I am reading was published in 2012 by Floris Books and is a reprint of a translation by Caroline Newton from 1928.

The story begins with a description of Caspar, a seventeen year-old boy, entering Nuremberg on foot one day in May 1928; he can barely talk and barely walk and seems to be surprised even by the movement of his own body. He has with him a letter bearing the address of Cavalry Captain Wessenig. He is taken to the police office where he is unable to answer any questions but is just able to scrawl his name on a piece of paper. He refuses all food except bread and water. Although he is dressed like a peasant it is noted that he has a fine white skin and looks ‘more like a young lady of aristocratic birth than a peasant.’ A doctor examines Caspar and also notes the lack of callouses on his feet.

The story begins with a description of Caspar, a seventeen year-old boy, entering Nuremberg on foot one day in May 1928; he can barely talk and barely walk and seems to be surprised even by the movement of his own body. He has with him a letter bearing the address of Cavalry Captain Wessenig. He is taken to the police office where he is unable to answer any questions but is just able to scrawl his name on a piece of paper. He refuses all food except bread and water. Although he is dressed like a peasant it is noted that he has a fine white skin and looks ‘more like a young lady of aristocratic birth than a peasant.’ A doctor examines Caspar and also notes the lack of callouses on his feet.

“One thing is evident,” his testimony concludes, “we are dealing with a person who has no conception of his fellow men, does not eat, does not drink, does not feel, does not speak like others, does not know anything of yesterday or to-morrow, does not grasp time, does not know he is alive.”

The story of the boy attracts a lot of attention from the populace who wish to see this curiosity; some believe him to be a wild man reared by wolves whilst others believe that he’s deceiving them. The unsigned letter that Caspar had on him was apparently written by his guardian who claims to have taken in him as a baby in 1815—his mother is unknown. He claims to have kept Caspar hidden away indoors so that no-one in the village knew of his existence and that he brought Caspar to Nuremberg in the night. Caspar knows neither the name of his guardian nor the name of the village whence he came. He says that ‘if you don’t want to keep him you will have to kill him and hang him up the chimney.’

The local teacher, Professor Daumer, becomes increasingly interested in Caspar and he tries to help him learn to talk. Surprisingly Caspar is quick to learn and he eventually tells Daumer what he can of his life so far.

So far as Caspar could remember he had always been in the same dark space, never anywhere else, always in the same space. Never had he seen a man, never had he heard his step, never had he heard his voice, never the song of a bird, never the cry of an animal; he had never seen the rays of the sun, nor the gleam of moonlight. He had never been aware of anything except himself, and yet he had known nothing of himself, never becoming conscious of loneliness.

In the mornings he had had fresh bread and a pitcher of water by his bed. On occasions the water tasted strange and caused him to fall asleep, when he awoke he would find his hair cut, his nails clipped and fresh straw on his bed. He had a wooden horse as his only toy. One day a man entered his room and for three days taught Caspar how to write his name. On subsequent nights the man led Caspar outside and taught him how to walk and then one night the man led him to Nuremberg and handed Caspar a note.

As the story of Caspar becomes known more widely it is not long before stories emerge of him being of noble blood, that he was kept in a dungeon to keep him out of the way so that an illegitimate heir could claim Caspar’s rightful place. Before long Caspar is moved from his cell to live with Professor Daumer but is ultimately under the protection of von Feuerbach, the president of the court of appeals. And so Caspar begins to learn about the world; the sun is especially fascinating to him, at one point he asks Daumer ‘is the sun God?’

But Daumer is in a bit of a quandary as he sees Caspar as an innocent and regrets that he has the task of exposing him to the cruel world. Daumer has to protect Caspar from the talk about his supposed noble lineage or the other claims of him being a swindler and yet at the same time he is compelled to parade him in front of his guests. During this period characteristics of Caspar’s personality emerge that will persist throughout the novel: he is fascinated with learning the identity of his mother, he is accused of lying by others, he refuses to let others read his diary. These all seem quite natural, especially as everyone seems to feel that they have a claim on him, that Caspar is there for their benefit and that he has no right to a personal life; his lying, his ‘secrecy’ just seem to me to be attempts to get away from this public life that everyone is intent on inflicting on him.

Events take a more sinister turn when one day he is attacked. In the garden one day he hears a voice from behind him say ‘Caspar, you must die’ and he is struck on the forehead with a knife. He made his way into the house and is later found in the cellar bleeding. Caspar recovers and it is during this period that an English lord first appears on the scene making enquiries about Caspar and offering a reward for anyone with information of Caspar’s attacker. Daumer, by this point, has become weary of looking after Caspar and it is agreed that he will go to live with the Beholds. Frau Behold is particularly obnoxious and domineering, Herr Behold is mostly absent. She bosses Caspar about and is only interested in him as a toy doll to parade around with at gatherings. She discourages his studies and teases him when he shows compassion towards slaughtered animals.

No, Caspar did not feel in the least at home. Frau Behold was utterly incomprehensible to him; her glance, her speech, her manner, all repelled him greatly. It cost him much thought and artifice not to show his dislike, although he was sick and miserable when he had spent only an hour in her company.

Relations deteriorate quickly between Caspar and Frau Behold. One morning he wakes to discover his caged blackbird dead on the dressing-table with its heart next to it on a plate. Caspar moves in with Herr von Tucher after Frau Behold locks Caspar out of her house.

At 467 pages this is quite a long novel, and as I have had to spend quite a while on the preliminary events I shall cover the rest of the novel in a second post.

The novel, so far, gives a pretty straightforward account of events, we could almost say that it’s Caspar’s version. But later on we get to see glimpses of others’ views and opinions.

Have you read the Wassermann novel? or seen the Herzog film?

I saw the film some years ago. I know exactly what you mean about measuring fiction against the non fiction information

LikeLiked by 1 person

I shall probably end up reading a non-fiction work on the subject but for now I’ve just been referring to the Wikipedia article occasionally. The novel will do for now.

LikeLike

I’m too obsessive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve seen the film a few times Bruno s was such a unique actor

LikeLiked by 1 person

I intend watching the film again after I finish this book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think it is on bfi player was when I subscribed

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: German Literature Month VII: Author Index | Lizzy's Literary Life