The Hundred Days was originally published in 1935 as Die Hundert Tage and the title refers to the famous period when Napoleon Bonaparte returned to Paris from his exile on the Mediterranean island of Elba to once again rule as Emperor of France. He arrived in Paris on 20th March 1815, whilst the Congress of Vienna was in full swing, and reigned as Emperor until he surrendered a little while after his defeat at the Battle of Waterloo.

The novel is split into four parts: the first and third parts are close-ups of Napoleon when he’s arriving in Paris in March and following his defeat at Waterloo respectively. The second and fourth parts concern the life of a laundress who is employed within the Emperor’s household and who idolises him.

The novel is split into four parts: the first and third parts are close-ups of Napoleon when he’s arriving in Paris in March and following his defeat at Waterloo respectively. The second and fourth parts concern the life of a laundress who is employed within the Emperor’s household and who idolises him.

At first this seems like a strange structure for a short novel about this period and I was a little dubious of whether it was going to work but by the end of the novel I was convinced – it’s just that it wasn’t quite what I was expecting.

Book One opens in Paris – the King has fled and the Emperor has arrived to a rapturous reception. Roth explains why the populace loved him:

They loved him because he seemed to be one of them – and because he was none the less greater than them. He was an encouraging example to them.

Roth also gives us a quick summary of Napoleon’s character:

He promised the people liberty and dignity – but whoever entered into his service surrendered their freedom and gave themselves completely to him. He held the people and the nations in low regard, yet none the less he courted their favour. He despised those who were born kings but desired their friendship and recognition. He believed in God yet did not fear Him. He was familiar with death but did not want to die. He placed little value upon life yet wished to enjoy it. He had no use for love but wanted to have women. He did not believe in loyalty and friendship yet searched tirelessly for friends. He scorned the world but wanted to conquer it anyway.

Back in his imperial palace Napoleon sets about forming a new cabinet, he sees his family, especially his mother, sees a fortune teller, he inspects his army and prepares for war against the expected Allied attack.

He envied his enemy, the lethargic old King who had fled with his arrival. The King had ruled in God’s name and through the strength of his ancestors alone had kept the peace. He, however, the Emperor, had to make war. He was only the general of his soldiers.

We get to see the Emperor, quite often, when he is alone and so one time, whilst walking in a park he hears someone nearby and becomes fearful of an assassination. But it is only a laundress, who can barely answer his questions; we do discover that her name is Angelina Pietri and that she is originally from Corsica, as is the Emperor, and he takes a note of her name. In the following days he studies maps, reviews his troops and prepares for war. When he’s reviewing his troops he notices a drummer boy, calls him over and discovers that the boy is called Pascal Pietri. He remembers Angelina’s surname and confirms that she is Pascal’s mother. Pascal corrects Napoleon when he assumes that Pascal’s father has the surname Pietri, instead it is Levadour. We see the human side of Napoleon here.

He remembered Angelina Pietri, the little housemaid whom he had seen in the darkness of the park. The memory cheered him, and the name Angelina, her little son who beat the drum in his army, and the brave freshness with which the boy had corrected him about his father’s name nearly moved him. Yes, these were his people, these were his soldiers!

Book One ends with Napoleon going off to battle.

Book Two is titled ‘The Life of Angelina Pietri’ and so we learn how Angelina moved to Paris, how she got a position as a servant in the Imperial household through her aunt, Véronique Casimir. As she cleans, the Emperor is often present, though always in another room. There’s one curious passage where Angelina is asked to a room, given a drink and asked to wait. She waits, drinks some wine, inspects some paintings, waits and then falls asleep. She’s woken in the morning when the Emperor enters the room brusquely and she is dismissed. The reason for her being there is not explained though we can probably guess. Anyway it’s a mix up as the Emperor calls his servant an ‘idiot’.

In Book Two we also learn about Angelina’s relationship with the Sergeant-Major Sosthène Levadour. Angelina discovers that she is pregnant but wants nothing to do with the father, she certainly doesn’t want to marry him. Angelina doesn’t love Levadour, she loves the Emperor.

All across the land and the world, women loved the Emperor. But to Angelina it seemed that to love the Emperor was a special and mysterious art; she felt betrothed to him, the most exalted lord of all time.

Her son is, of course, Pascal. From this point on the tale of Angelina becomes more interesting, at least it did for me, as Book Two covers the period up to Napoleon’s abdication and the reinstatement of the monarchy under Louis XVIII.

I’ve probably revealed more of the plot than I’d originally intended so I’ll just say that we’re also introduced to one of the more loveable characters in the novel, Jan Wokurka. Books One and Two cover about two thirds of the novel. In Book Three we see the events following Waterloo from Napoleon’s perspective. There’s a wonderful scene in this section that takes place on the battlefield but I won’t reveal any more. Napoleon appears weaker, less sure of himself, and often just wants to give up – he’s truly defeated. With the final book we’re back with Angelina and we follow her fate during Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo. Be warned there’s an unexpected ending.

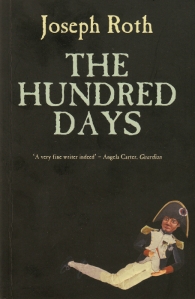

I read the translation by Richard Panchyk, published by ‘Peter Owen’ in 2011 and pictured at the head of this post. This was the first English translation for seventy years. This translation has recently been published in the U.S. by ‘New Directions’. I prefer the New Directions cover as it demonstrates that the focus of the novel is more on Angelina than on Napoleon directly but the Peter Owen cover makes a bit more sense when you’ve read the book.

I read the translation by Richard Panchyk, published by ‘Peter Owen’ in 2011 and pictured at the head of this post. This was the first English translation for seventy years. This translation has recently been published in the U.S. by ‘New Directions’. I prefer the New Directions cover as it demonstrates that the focus of the novel is more on Angelina than on Napoleon directly but the Peter Owen cover makes a bit more sense when you’ve read the book.

I liked the parts of the book with the laundress best. It helps us understand why the common people loved Napolean. Far from Roth’s best work but very much worth reading.

LikeLike

Yes, the parts with the laundress help us understand the effect that Napoleon had on others. I feel that Roth could have got into Napoleon’s mind a bit more. Still, I enjoyed it…and I must read more by Roth.

LikeLike

I really did mean to

Read some Joseph Roth during German Lit month ….but time ran out ! He very much remains on my radar . Thanks for the fascinating review.

LikeLike

Thanks hastanton. I know what you mean. There were several books that I wanted to read but I just didn’t get the time. I mean to read some more books by Joseph Roth (and Stefan Zweig) as well in 2015.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful review, Jonathan. I didn’t know that Philip Roth wrote a book on Napoleon. After reading your review, I am inspired to read this book. I loved that passage about Napoleon’s character – how he is a bundle of contradictions. Such a beautiful passage.

LikeLike

Thanks Vishy. That quote actually goes on for a bit longer but I cut it off as I thought the point was made. It works well by concentrating on the laundress though I didn’t think so at first.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Radetzky March Readalong: Part One | Intermittencies of the Mind